Flood Insurance in a Dying Delta

Last week, a story on NPR discussed soaring federal flood insurance premiums in coastal communities in the United States. Particularly shocking was the story of one man’s rates set to rise from $633 per year to $28,000 per year. Anything you could possibly say about an increase like that is going to be an understatement.

These sharp rate hikes are the result of the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act, passed by Congress in June of 2012. The law attempts to make the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) solvent after crippling losses from the 2005 hurricane season—think: Mmes. Katrina, Rita, and Wilma—left it with $21 billion in debt.

Biggert-Waters has several provisions intended to reform the program, but two stand out in particular:

- It requires that subsidized flood-insurance rates be replaced by risk-based rates. Previously, not all property owners paid premiums proportional to their risk, leaving the NFIP holding the bag. Biggert-Waters changes that.

- The NFIP was working with flood maps that in some cases hadn’t been updated since the 1980s. Biggert-Waters requires the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to finally update the nation’s flood insurance rate maps. Part of those revisions involves accounting for what are termed “other inclusions.” These are basically things that went ignored in previous flood maps. You know, like rising sea levels, changes in annual rainfall, and increasing hurricane intensity. Interestingly, any reference to the words “climate change” was stripped from the final bill.

Both of these provisions seem to make a lot of sense, but they also dramatically affect residents throughout the coastal United States.

And the impact in Louisiana is especially pronounced. Let’s look again at NPR’s story and the guy with the 4000%-plus spike in his premiums. Here’s the transcript:

One man in particular, who is an insurance agent down there, and what he found was his rate has been $633 a year. And instead, it was going to go up to $28,000 a year, which was just unaffordable for him. And part of what happened to him is he’d built his home 15 years ago, and the federal government told him how high to build it. And he said, well, OK, to be safe, I’ll build it two feet higher than that.

And then new maps are coming out. They’re not final yet but the new maps now tell him that 15 years ago he was wrong and he should have built six feet higher than what he actually built. And so, he has to either elevate his home by six feet, which would be unaffordable, or else pay the $28,000 a year.

While there are plenty of stories about coastal communities all around the US that are anxious about the impact of flood-insurance reform, coastal Louisiana is a special case. Flood maps for the region are attempting to capture a phenomenon that is even more dynamic than in other regions similarly affected by rising sea levels (or anything else climate change has to offer). That’s because much of coastal Louisiana is sinking into the Gulf even more rapidly than those waters are rising. The boundaries of this particular region’s coastal flood zones are rapidly on the move.

Why is that? As I’ve discussed previously on this blog (see here, here, and here), coastal Louisiana is a very young, very flat, very muddy landscape. It got built out into the Gulf of Mexico thanks to about 7,000-8,000 years of accumulating Mississippi River Sediment. And it only exists insofar as the amount of sediment the river deposits is greater than the amount that gets washed away.

Now, ever since New Orleans was first settled in 1718, people have been trying to carve out a livelihood from this mucky, dynamic place. Part of that involved erecting more and more miles of continuous levees along the river to protect their investments and way of life. And part of that involved the rise of several extractive industries, the most recent and notable of which would be oil and natural gas.

But all that leveeing and extraction has had a massive impact on the deltaic landscape.

Today, the river is so continuously and impermeably leveed, it almost never floods beyond its banks. Instead of replenishing soils in the coastal wetlands, the vast majority of the Mississippi River’s land-building sediments get funneled straight into the gulf of Mexico (if they’re not already trapped behind dams somewhere upstream).

Meanwhile, the oil and gas industry’s thousands of miles of pipelines and transportation canals have helped accelerate the erosive powers of the Gulf’s storms and waves. All that pipeline and canal development not only devoured their share of the state’s southern wetlands, but also provided inlets for Gulf saltwater to intrude into freshwater ecosystems.

Saltwater, of course, kills off freshwater vegetation and as those plants die, they relinquish sediments formerly grasped by their roots. The oil and gas industry’s perforations have helped transform thousands of square miles wetland into just plain old wet. And without river floods to replace all that lost sediment, southern Louisiana will just keep crumbling and sinking into the Gulf.

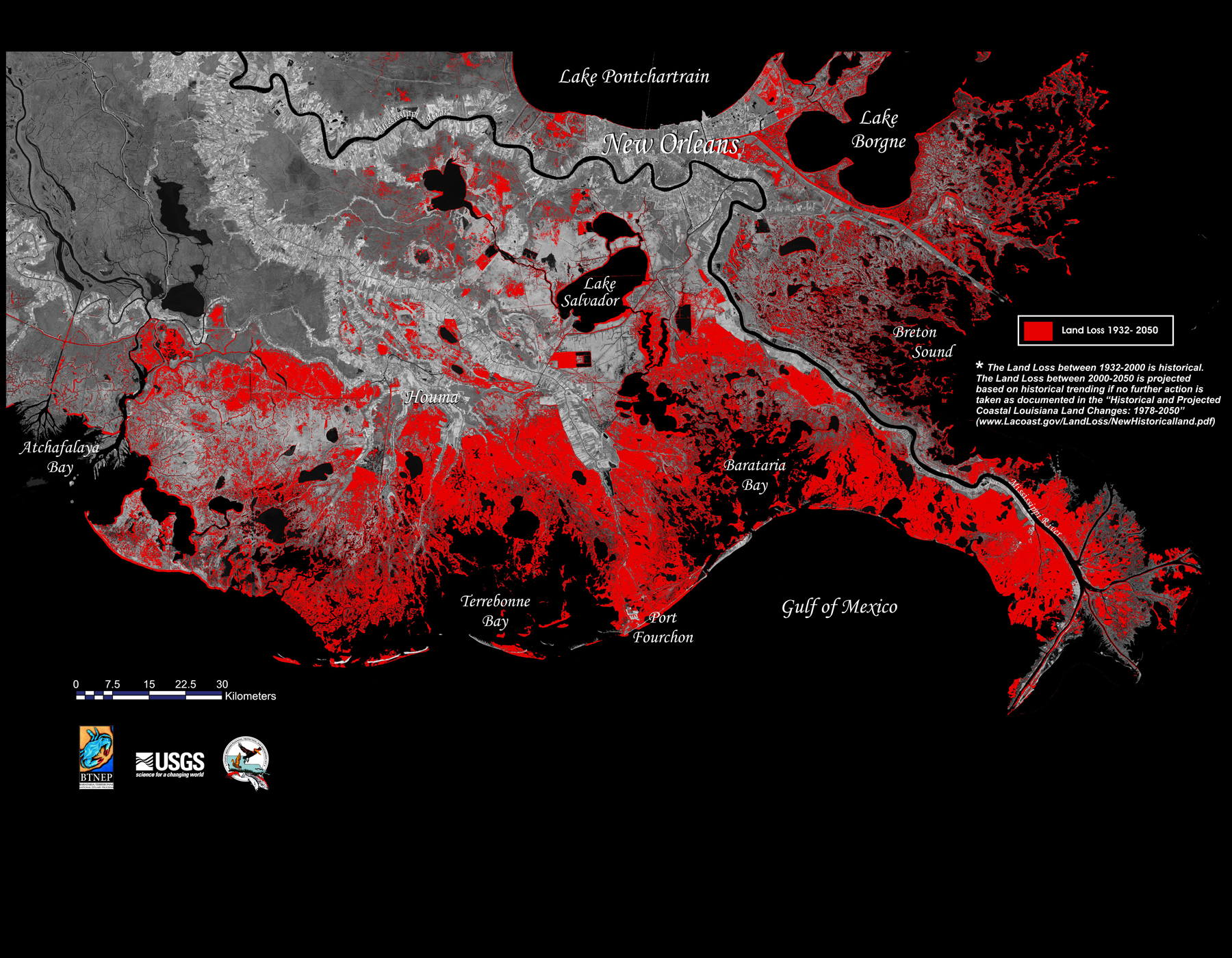

Below you can see a map of current and projected land loss in Louisiana through 2050. Anything marked in red either is, or will be, open water. It’s pretty horrifying.

Just to quantify this mess: since 1932, an area about the size of Delaware (about 2000 square miles) has been converted to open water and the state continues to lose around another 20 square miles per year.

Which brings me back to the guy being asked to pay a $28,000 flood-insurance premium. That man was told he should have built his home 6 feet higher than he did in 1998. But that new calculation is not just a result of better maps that take things like sea-level rise into account, as the NPR story suggested. It’s also because the landscape itself has changed that much in just 15 years.

And yet nowhere in this discussion was there any mention of Louisiana land loss, probably one of the nation’s biggest, yet least talked-about environmental catastrophes.

Resources on Louisiana Land Loss (ordered alphabetically)

Books

Richard Campanella’s Delta Urbanism

Mike Tidwell’s Bayou Farewell

Websites

Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana

LSU Coastal Sustainability Studio

Times-Picayune interactive graphic, “The Rise and Disappearance of Southeast Louisiana”

3 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] are eating southern Louisiana from the inside out, contributing significantly to shocking rates of land loss: 2,000 square miles of the state’s coastal wetlands have been converted to open water since […]

[…] kinds of ideas are also developing in Louisiana, where sea-level rise is combining with sinking and eroding coastal wetlands to make for a particularly sodden […]

[…] kinds of ideas are also developing in Louisiana, where sea-level rise is combining with sinking and eroding coastal wetlands to make for a particularly sodden […]